Agriculture

The most recent and complete agriculture model documentation is available on Pardee's website. Although the text in this interactive system is, for some IFs models, often significantly out of date, you may still find the basic description useful to you.

The IFs agriculture model tracks the supply and demand, including imports, exports, and prices, of three agricultural commodities: crops, meat, and fish. Crops have direct food, animal feed, and industrial uses. Meat and fish have only food use. The agriculture model is also where land use dynamics and water use are tracked in IFs, as these are key resources for the agricultural sector.

The structure of the agriculture model is very much like that of the economic model. It combines a growth process with a partial economic equilibrium process using stocks and prices to seek a balance between the demand and supply sides. As in the economic model, no effort is made in the standard adjustment mechanism to obtain a precise equilibrium in any time step. Instead stocks serve as a temporary buffer and the model chases equilibrium over time.

The most important linkages between the agriculture model and other models within IFs are with the economic model. The economic model provides forecasts of average income levels, labor supply, total consumer spending, and agricultural investment, as well as parameters such as the capital elasticity of substitution, all of which are used in the agriculture model. In turn, the agriculture model provides forecasts on agricultural production, imports, exports, and demand for investment, which override the sectoral computations in the economic model. The agriculture model also has important links to the population and health models, using population forecasts and providing forecasts of calorie availability.

Structure and Agent System: Agriculture

System/Subsystem

|

Agriculture

|

Organizing Structure

|

Partial market equilibrium

|

Stocks

|

Capital, labor, accumulated technology, agricultural commodities, land

|

Flows

|

Production, loss, consumption, trade, investment

|

Key Aggregate Relationships (illustrative, not comprehensive)

|

Production function with endogenous technological change Price determination |

Key Agent-Class Behavior Relationships (illustrative, not comprehensive)

|

Household crop, meat, and fish consumption Industry crop use Livestock producers crop use |

Dominant Relations: Agriculture

Agricultural production is a function of the availability of resources, e.g. land, livestock, capital, and labor, as well as climate factors and technology. Technology is most directly seen in the changing productivity of land in terms of crop yields, and in the production of meat relative to the input level of feed grain. The model also accounts for lost production (such as spoilage in the fields or in the food supply chain), which is determined by average income.

Agricultural demand depends on average incomes, prices, and a number of other factors. For example, changing diets can affect the demand for meat, which in turn affects the demand for feed crops. The industrial demand for crops, some of which is directed to the production of biofuels, is also affected by energy prices.

Production and demand, along with existing and desired stocks and historical trade patterns determine the trade in agricultural products. The differences in the supply of crops, meat, and fish (production after accounting for losses and trade) and the demand for these commodities are reflected in shifts in agricultural stocks. Stock shortages feed forward to actual consumption, which is addressed in the population model of IFs. Stocks, particularly changes in stocks, are a key driver of changes in crop prices. Crop prices are also influenced by the returns to agricultural investment and therefore to the basic underlying cost structure. Meat prices are tie to, and track crop prices, while changes in fish prices are driven by changes in fish stocks.

Stocks and stock changes also play a role, along with general economic and agricultural demand growth, in driving the demand for agricultural investment. The actual levels of investment are finalized in the economic model of IFs and subject to constraints there. The investment can be of two types – investment for expanding and maintaining cropland (extensification) and investment for increasing crop yields per unit area (intensification). The expected relative rates of return determine the split.

The final key dynamics addressed in the agriculture model relate to land, livestock, and water. The latter of these is very straightforward, driven only by crop production. Changes in livestock are determined by changes in the amount of available grazing land, changes in the demand for meat, and the ability of countries to meet this demand as reflected in changing stocks.

In the IFs model, land is divided into 5 categories: crop land, grazing land, forest land, ’other’ land, and urban or built-up land. First, changes in urban land are driven by changes in average income and population, and draws from all other land types. Second, the investment in cropland development is the primary driver of changes in cropland, with shifts being compensated by changes in forest and "other" land. Third, changes in grazing land are a function of average income, with shifts again being compensated by changes in forest and "other" land. Finally, conservation policies can influence the amount of forest land, with any necessary adjustments coming from crop and grazing land.

Agriculture Flow Charts

Overview

The agriculture model combines a growth process in production with a partial equilibrium process that replaces the agricultural sector in the full-equilibrium economic model unless the user disconnects it. The model represents three agricultural commodities: crop, meat, and fish.

The key equilibrating variables are the stocks of the three commodities. Equilibration works via investment to control capital stock and via prices to control domestic demand.

Specifically, as food stocks rise, investment falls, restraining capital stock and agricultural production, and thus holding down stocks. Also, as stocks rise, prices fall, thereby increasing domestic demand, further holding down stocks. Domestic production and demand also influence imports and exports directly, which further affect stocks.

This section presents several block diagrams that provide an overview of the variables and dynamics of the agricultural model.

Agricultural Production

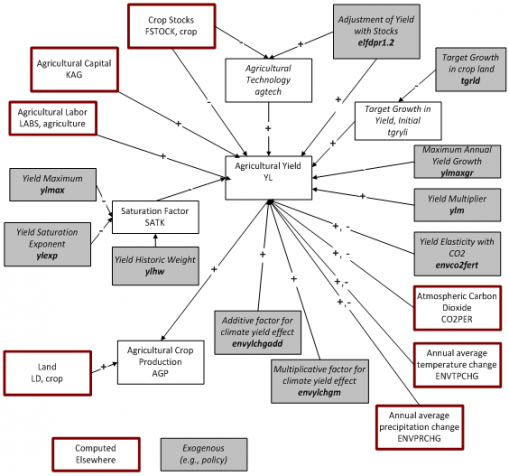

Crop Production

Crop production is most simply a product of the land under cultivation (cropland)

and the crop yield per hectare of land. Yield is determined in a Cobb-Douglas type production function, the inputs to which are agricultural capital, labor, and technical change. Technical change is conceptualized as being responsive to price signals, but the model uses food stocks in the computation to enhance control over the temporal dynamics of responsiveness. Specifically, technology responds to the imbalance between desired and actual food stocks globally. In addition there is a direct response of yield change to domestic food stocks that represents not so much technical change as farmer behavior in the fact of market conditions (e.g. planting more intensively). Overall, basic annual yield growth is bound by the maximum of the initial model year's yield growth and an exogenous parameter of maximum growth.

This basic yield function is further subject to a saturation factor that is computed internally to the model̶–investments in increasing yield are subject to diminishing rather than constant returns to scale. Moreover, changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) will affect agricultural yields both directly through CO2 and indirectly through changes in temperature and precipitation. Finally, the user can rely on parameters to increase or decrease yield patterns indirectly with a multiplier or to use parameters to control the saturation effect and the direct and indirect effects of CO2 on crop yield.

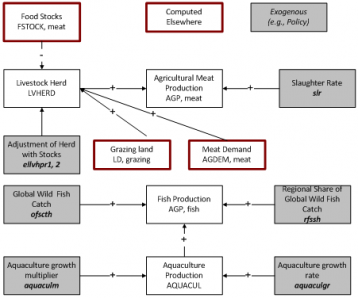

Meat and Fish Production

Meat and fish production are represented far more simply than crop p

roduction. Meat production is simply the product of livestock herd size and the slaughter rate. The herd size changes over time in response to global and domestic meat stocks, as well as changes in the demand for meat and the amount of grazing land.

Fish production has two components: wild catch and aquaculture. The former is based on global catch and the regional share, both of which are specified exogenously. Aquaculture is assumed to continue to grow at a country-specific growth rate; a multiplier can also be used to increase or decrease aquaculture production.

Agricultural Demand

Overview

Agricultural demand is divided into crops, meat, and fish. Crop demand is further divided into industrial, animal feed, and human food demand.

Meat and food demand are responsive to calorie demand, which in turn responds to GDP per capita (as a proxy for income). The division of calorie demand between demand for calories from crops and from meat changes in response also to GDP per capita (increasing with income).

When all components of agricultural demand are computed, the price of the food elements of it are checked to assure that the total household demand for food does not exceed a high percentage of total country-level household consumption expenditures.

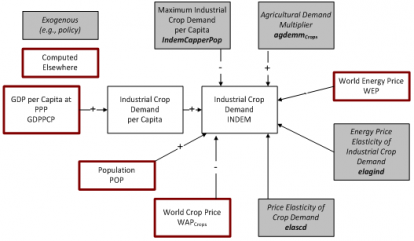

Industrial Crop Demand

Industrial crop demand (examples would be textile use of cotton or beverage inputs use of barley) is driven primarily by GDP per capita and population. Another important use in recent years has been for biofuels, and that demand component is responsive to world energy price and an elasticity.

Crop prices also influence total industrial agricultural demand. A maximum per capita demand parameter constrains the total and an exogenous multiplier allows users to alter the total. <header><hgroup>

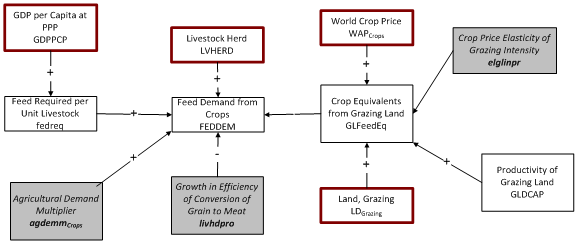

Animal Feed Demand for Crops

</hgroup></header>

The total feed demand for the livestock herd is dependent on the weight of the livestock herd and the per weight unit feed requirements. The per unit feed requirements increase with GDP per capita as populations move from meat sources such as ch

ickens to more feed intensive ones such as pork and especially beef. But they also are reduced by change in the efficiency of converting feed to animal weight.

Some of the food requirements of livestock are met by grazing, thereby reducing the feed requirements. The feed equivalent of grazing depends on the amount of grazing land, the productivity of that land (computed in the initial year and highly variable across countries), and grazing intensity (which increases with crop prices).

Finally, the feed demand can be modified directly by the same exogenous crop demand parameter that modifies industrial crop demand. <header><hgroup>

Calorie Demand

</hgroup></header> Crop use for food and meat demand are both influenced by calorie demand. Total per capita calorie demand is driven by GDP per capita, but can be limited by calorie availability as well as by an exogenous parameter specifying maximum calorie need.

The calculations of demand for meat and food crop determine the ultimate division of calorie sources (shown in other topics). Calories from meat are connected to the demand for meat in tons, with adjustments for the conversion of meat to crop equivalents and then crop equivalents to calories. There is also a limit to the share of calories that can come from meat. The demand for calories from crops is simply the residual obtained by subtracting the demand for calories from meat from the demand for total calories.