China Sub-Regional June 2017 Consolidation

Overview

China's sub-regional model has a total of 63 preprocessor series. Although there are 652 preprocessor series in the IFs model, there are many that are not applicable to sub-regional models or do not significantly impact forecasts; only 355 preprocessor series are sought for sub-regionalization. Thus China's sub-regional model has nearly 18% coverage at this point. There are a 29 preprocessor series that have been identified that could be pulled into the model. If this data was to be pulled the the total coverage of the model would increase to nearly 26%.

Below is a table that shows the module coverage for the China sub-regional model. Population has the most coverage, but this is also the fewest number of preprocessor series. The economy module has the second highest coverage, which is good. Population and Economy have the greatest impact on the model's overall behavior and coverage in these modules is important. Health and education are areas of weakness for the China sub-regional model. In part the weakness is driven by the large number of series in those modules. There is more education data available that could be brought into the model, but some of the data requires historical age-sex cohorts to calculate rates with the data. Health has low coverage because there is not a lot of health data that is available for free and in English. It appears that much of China's health data is proprietary and not publicly available, but there may be alternative sources available if a researcher searched in Mandarin.

| IFs Module | Preprocessor Series Pulled | Total Preprocessor Series | Module Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 7 | 8 | 87.5% |

| Economy | 24 | 55 | 43.6% |

| Health | 5 | 57 | 8.8% |

| Education | 8 | 91 | 8.8% |

| Agriculture | 11 | 36 | 30.6% |

| Energy | 7 | 66 | 10.6% |

| Infrastructure | 1 | 21 | 4.8% |

| Environment | 0 | 9 | 0.0% |

| Socio-Political |

0 | 12 | 0.0% |

| Total | 63 | 355 | 17.7% |

| Potential Series | 92 | 355 | 25.9% |

Population

China's Population

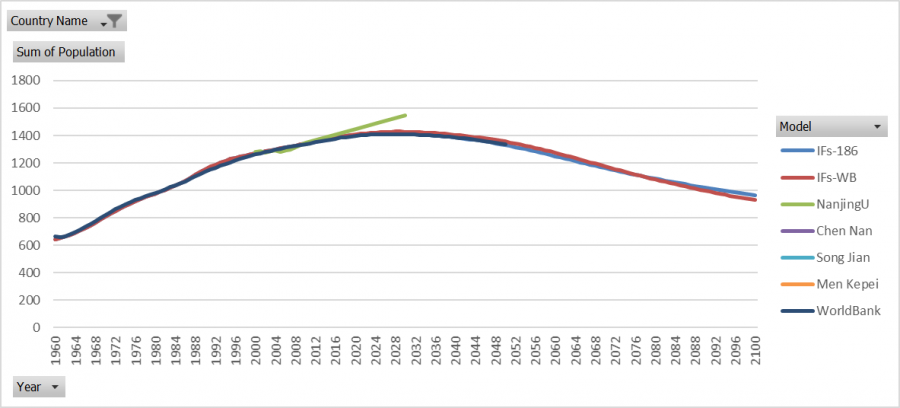

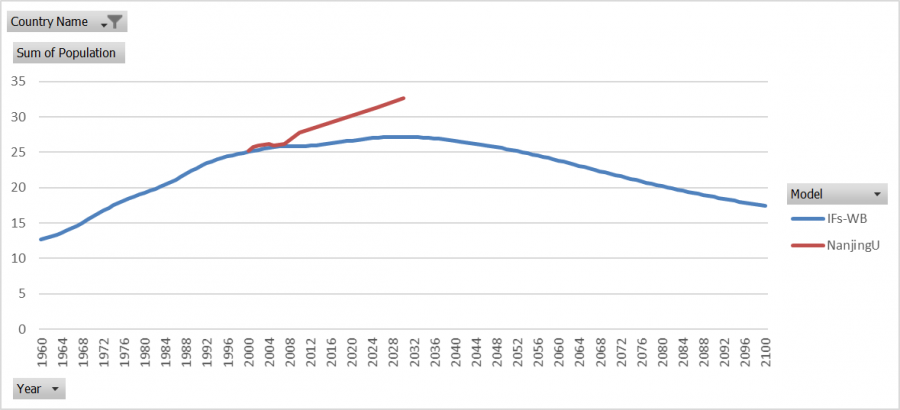

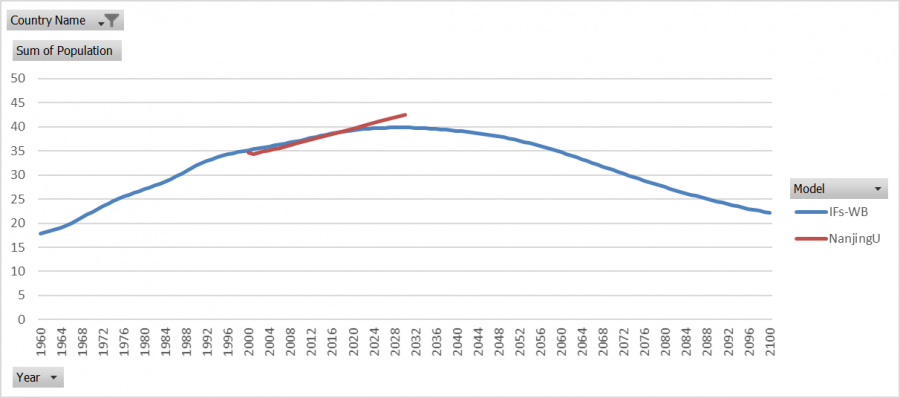

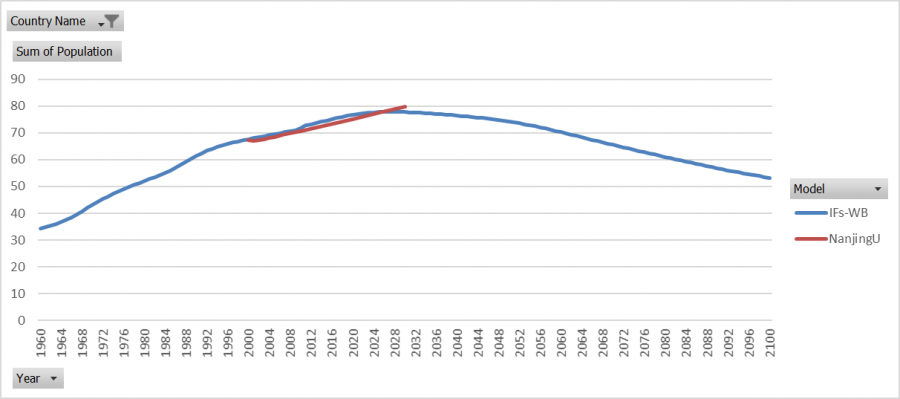

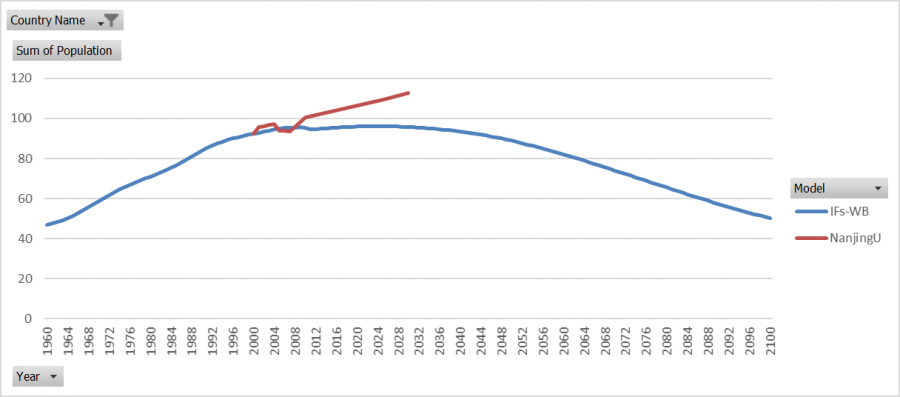

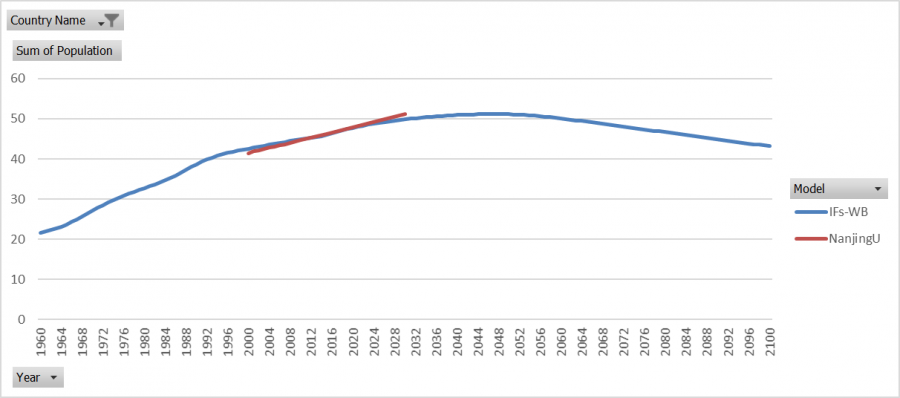

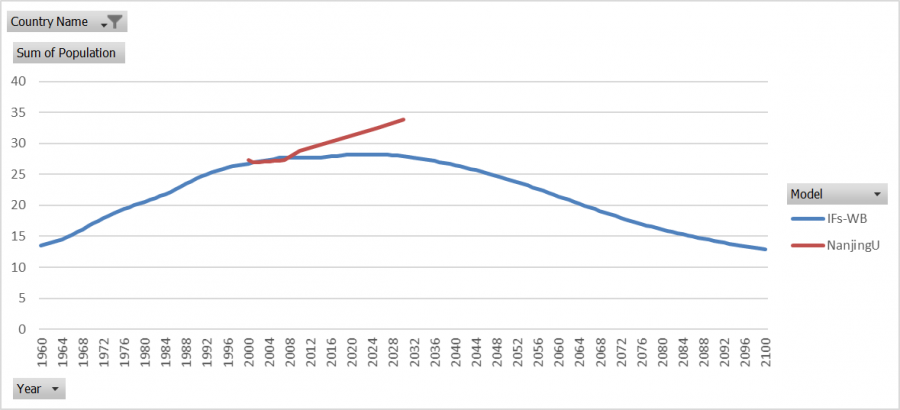

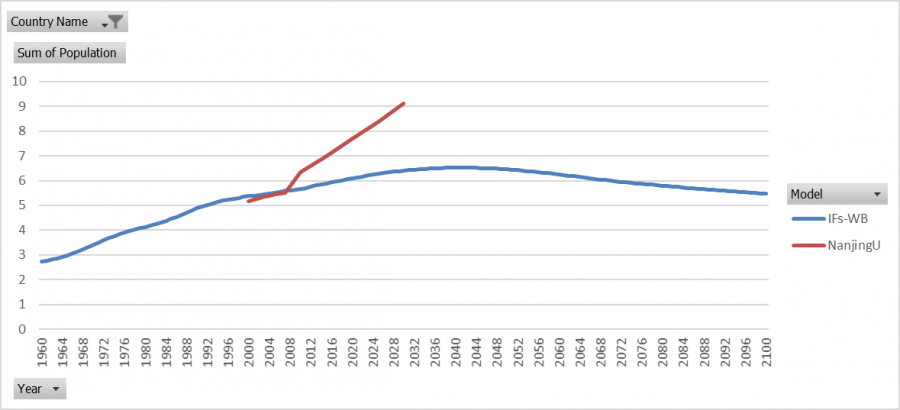

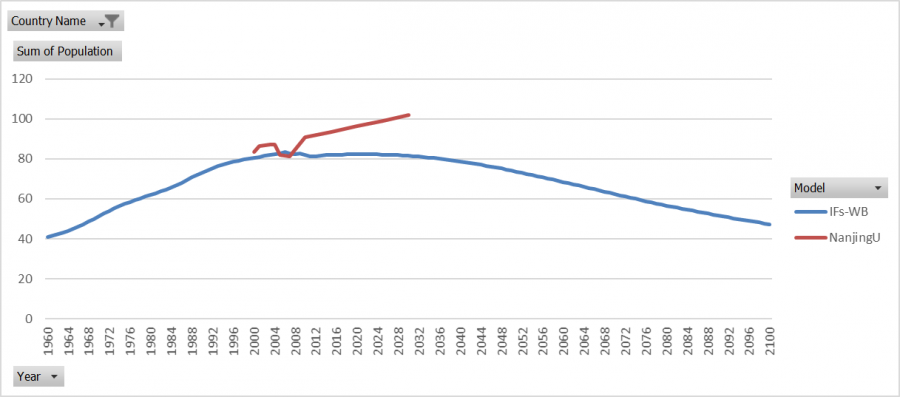

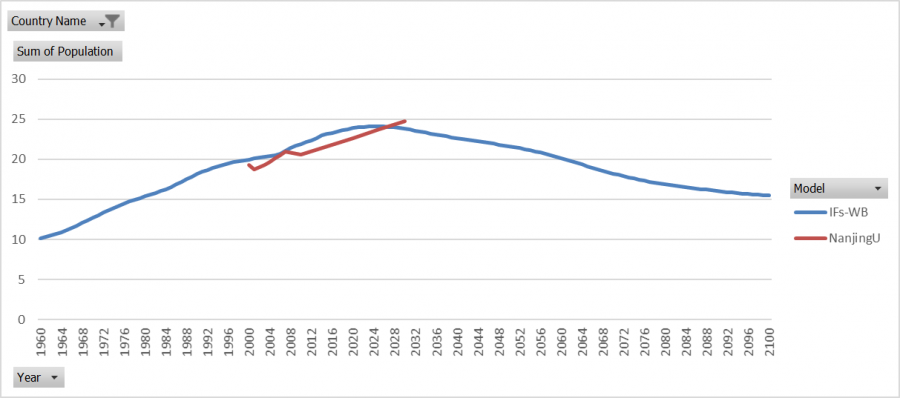

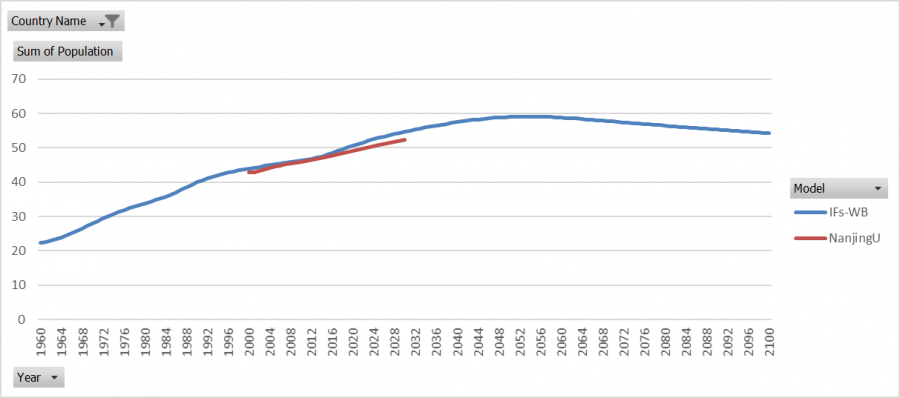

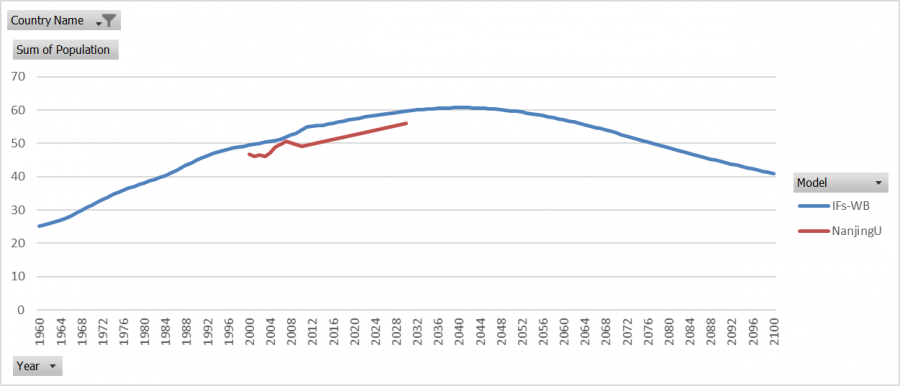

The provincial model's population for China was rolled up in IFs and compared to other population forecasts for China, as shown below. It is clear that the population forecast from the sum of the provinces (IFs_WB) is in line with other forecasting models. Nanjing University's forecasting model is the most off from the rest of the forecasts, where population growth is forecast to continue to rise.

It was difficult to find provincial forecasts on China, but there was one paper that was found in Mandarin that had provincial population forecasts for China's provinces. The paper from Nanjing University compared its forecasts to several other population forecasting models of China and this data was used to compare the IFs provincial model to. As was previously stated, Nanjing University's model has a steeper slope and forecasts population to continue to rise at the same rate, which all other forecasting models do not. This suggests that it might not be as good of a model as the others, but it gives some information about our forecasts.

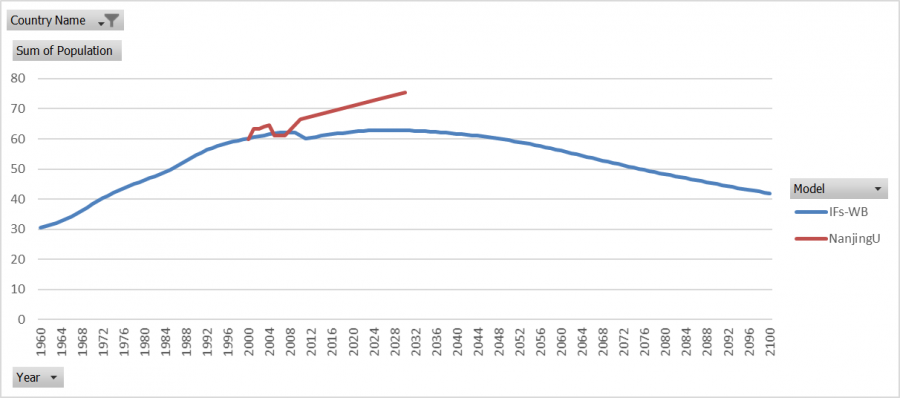

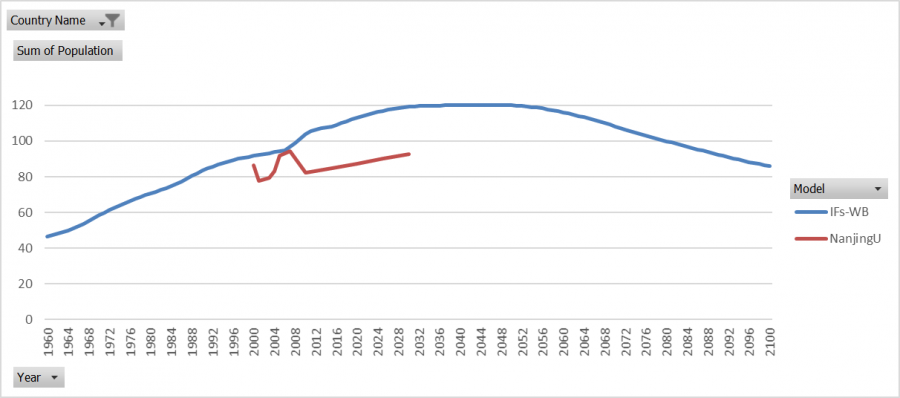

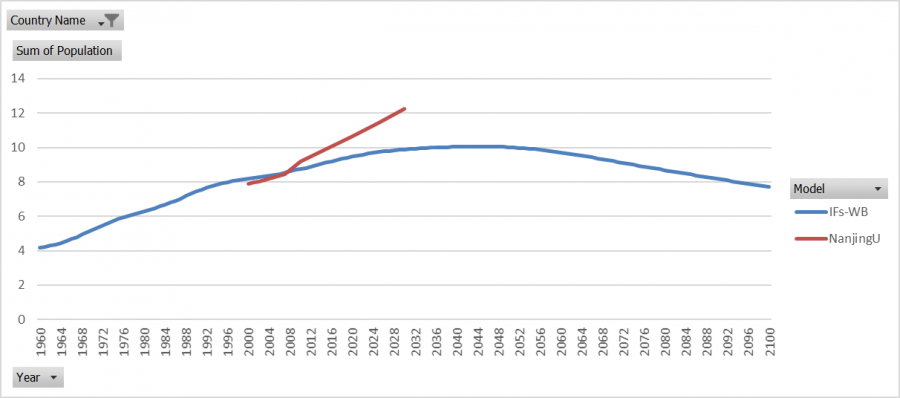

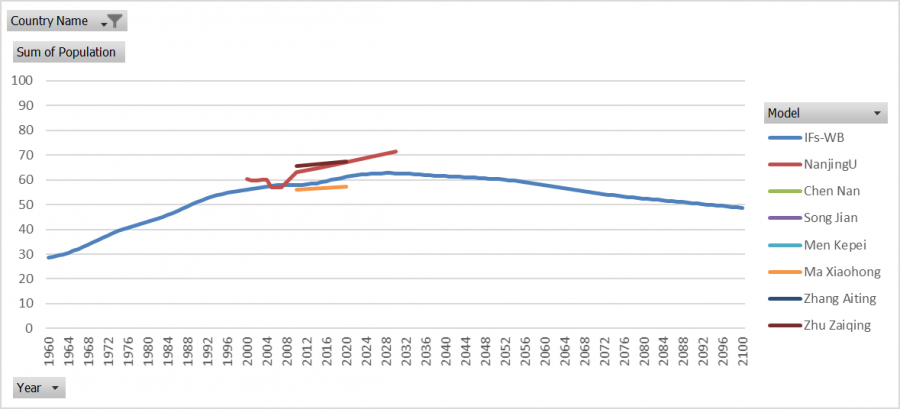

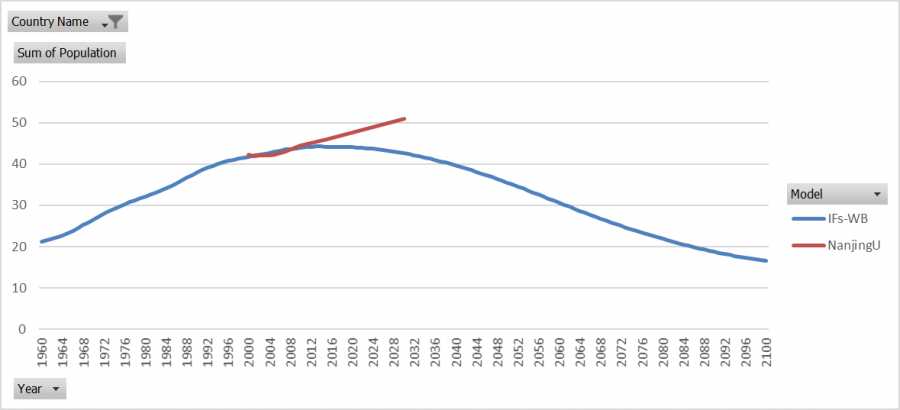

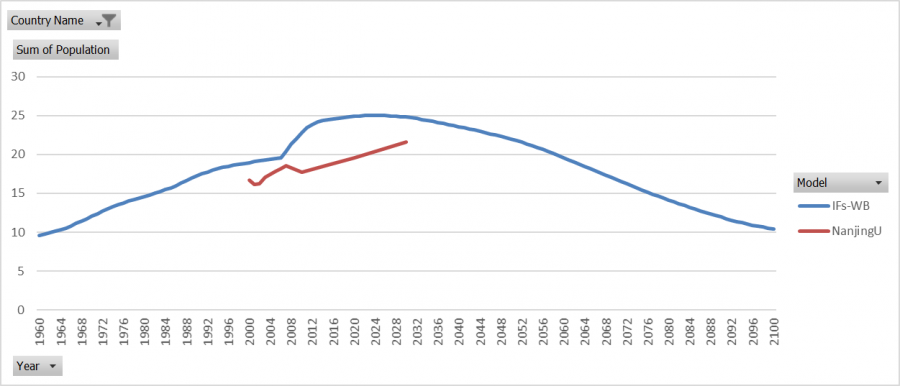

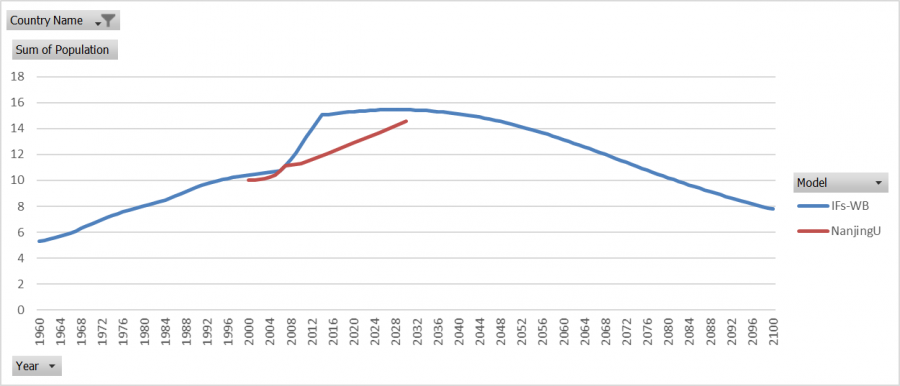

Anhui

Both model's historical data looks strange for Anhui, this is seen throughout the provinces and is in part due to the changing definitions of boundaries throughout China. However, the shifts do not coincide perfectly, it looks like Nanjing University's data is lagged. Because the paper is in Mandarin there is not any certainty that this is true.

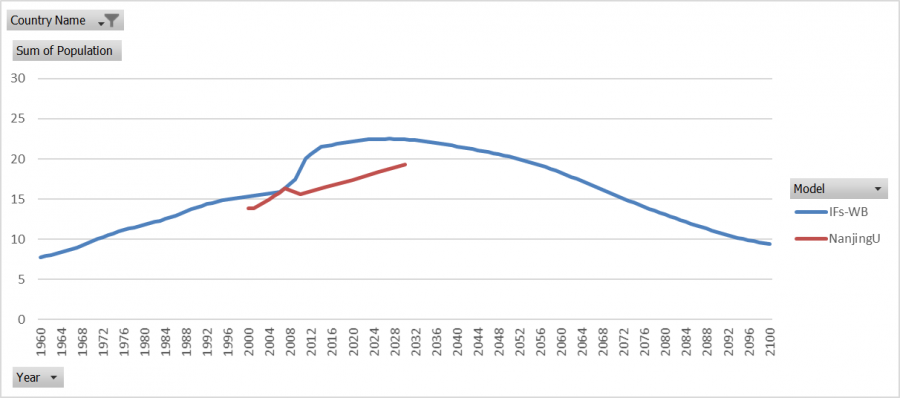

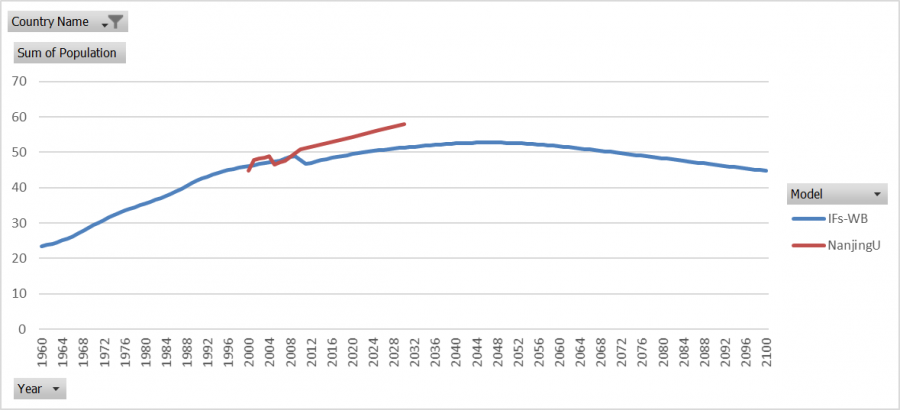

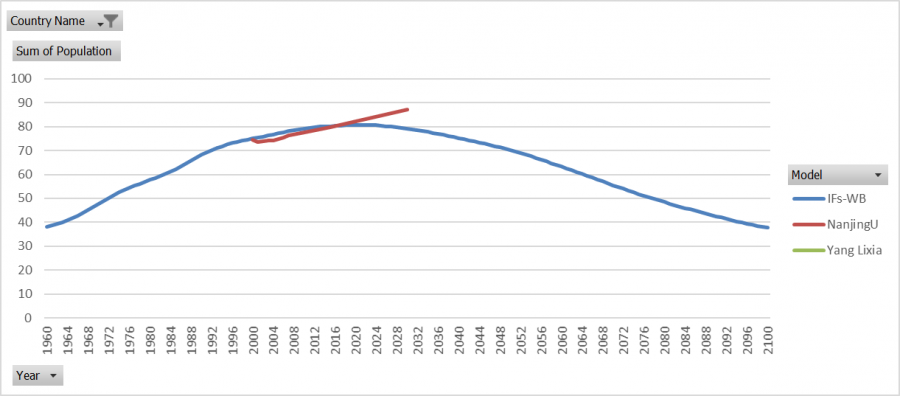

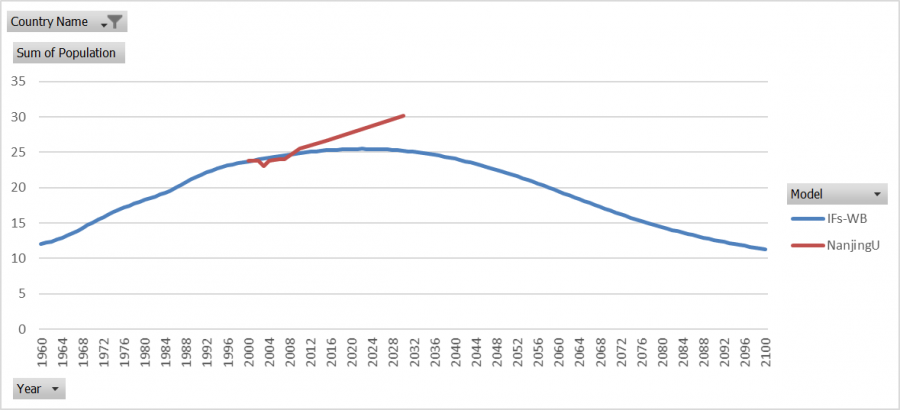

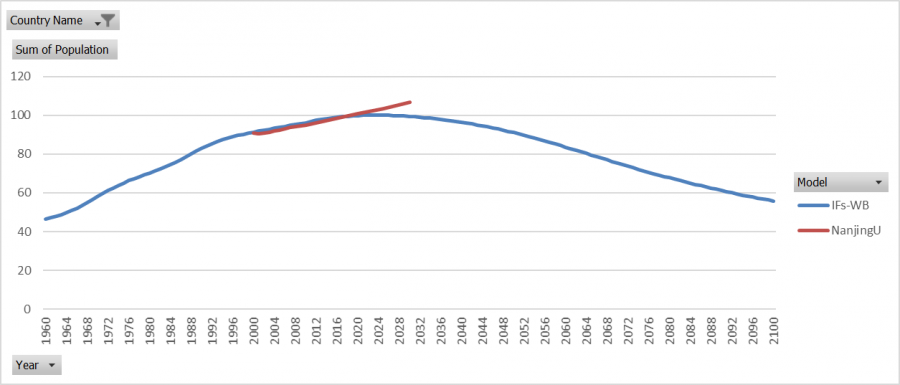

Beijing

Beijing has a large jump in the late 2000s in the World Bank data. Nanjing University's data decreases when the World Bank data is increasing in the late 2000s, which looks odd and perhaps is another sign that the data is lagged.

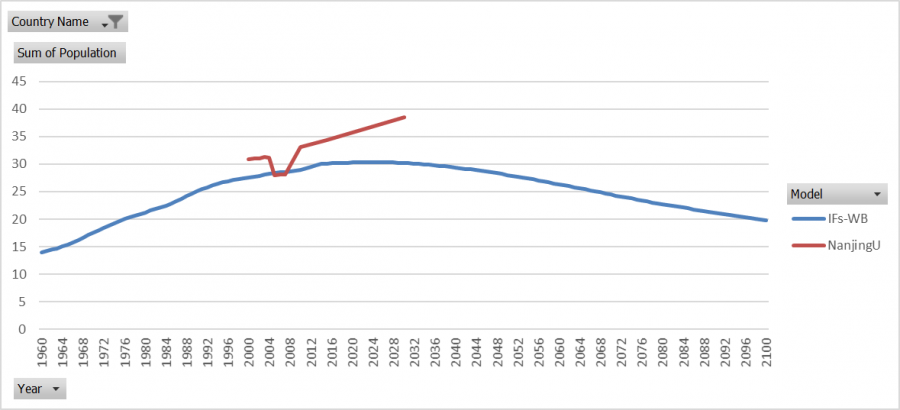

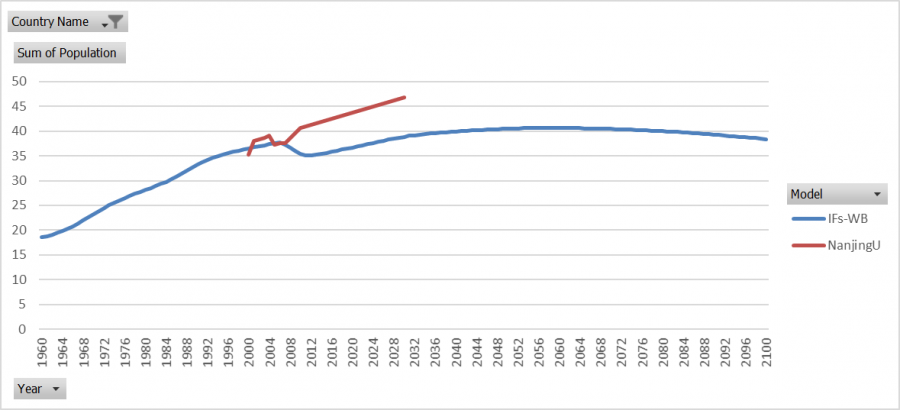

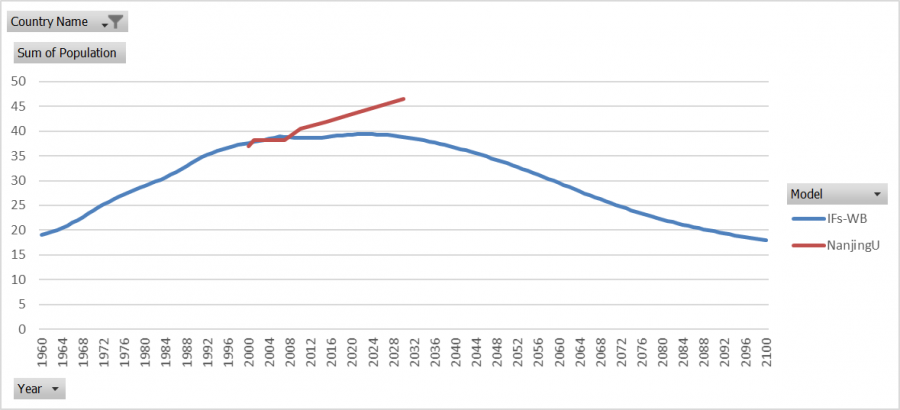

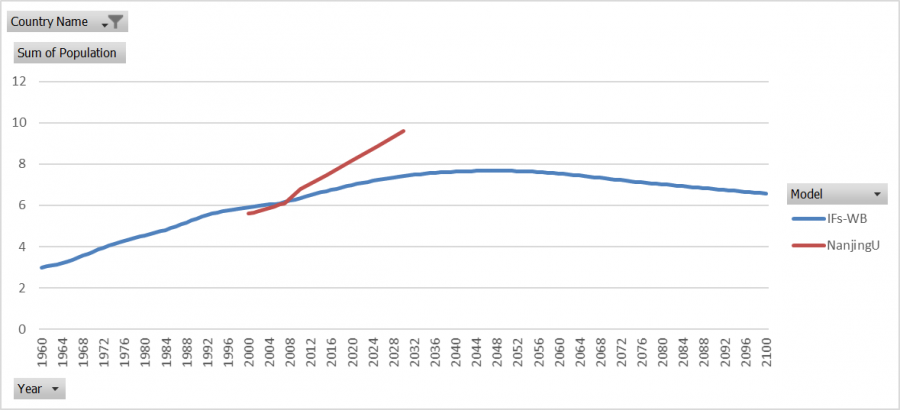

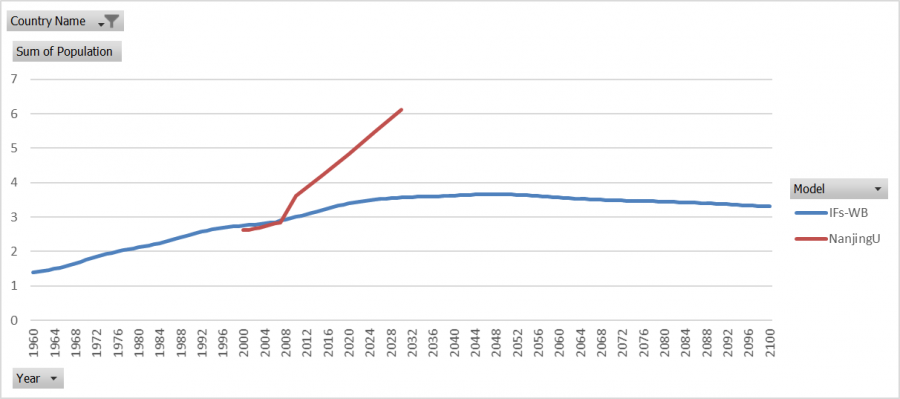

Chongqing

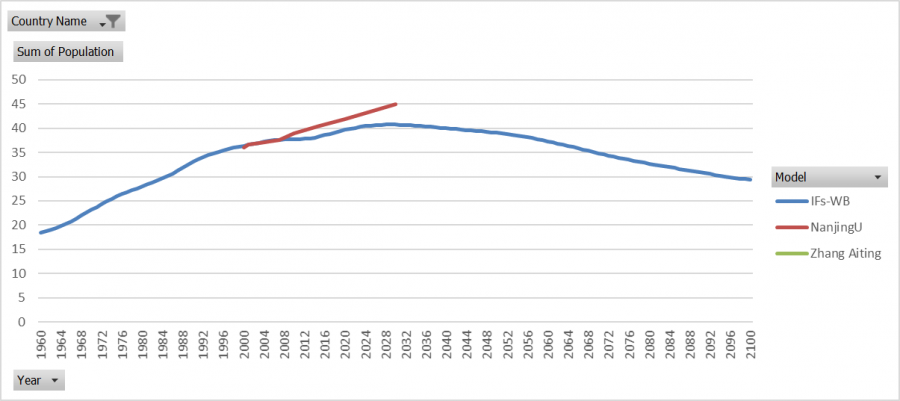

The World Bank data was interpolated in the model which fills the population back to 1960 smoothly. In reality the municipality did not bifurcate from Sichuan until 1997 and its borders were redefined several times between 1997 and 2008. Thus Nanjing University's historical data's strange behavior makes sense, but the forecasts look too high.

Gansu

Guangdong

Guizhou

Guangxi

Fujian

Hainan

Hebei

Heilongjiang

Henan

Hubei

Henan

Jiangsu

Jiangxi

Jilin

Liaoning

Nei Mongol

Ningxia

Qinghai

Shaanxi

Shandong

Shanghai

Shanxi

Sichuan

Tianjin

Tibet

Xinjiang

Yunnan

Zhejiang

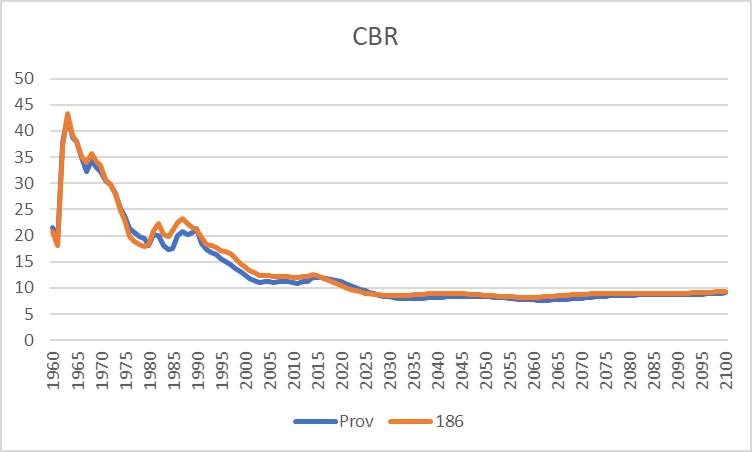

China's Crude Birth Rates

CBRs in the provincial model are quite close to the 186 model. There is a greater difference in the historical data than in the forecasts, but overall the two models are quite close.

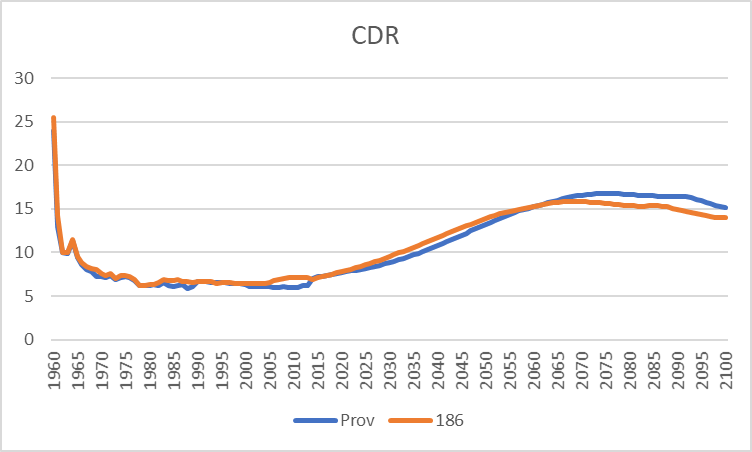

China's Crude Death Rates

Like CBRs, CDRs are quite close in the two models. There is a greater difference towards the end of the forecasts after 2065.

China's Migration Rates

Migration rates that have been included in the model are historical and were found in a paper[1] that estimates sub-national migration in China. Chinese intranational migration has proven to be a difficult measure because there is a significant amount of illegal migration from rural areas to urban areas.

There is only historical data available. Therefore the migration rates do not impact the forecasts because the model does not endogenously calculate migration forecasts.

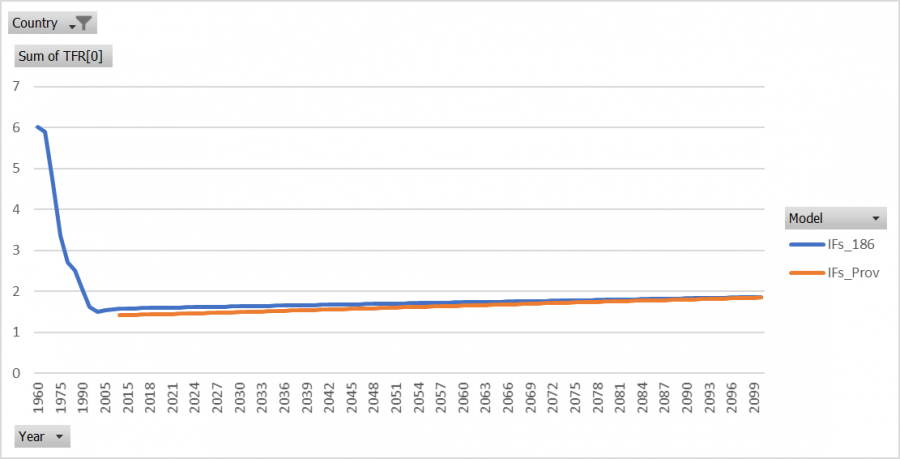

China's Total Fertility Rates

There is only a single year of historical data for provincial TFR in China and unfortunately the data is from 2000, making this series outdated. For all provinces except Beijing, the 2000 historical data point is the same as the 2014 data point when the model initializes. Due to the outdated data being used for model initialization the provincial model's forecasts of TFR are slightly lower than the 186 model initially.

It is also important to note that provinces such as Beijing are outliers compared to the rest of the world due to the impact of the One Child Policy in China's urban areas. Unlike the rest of the world where TFR is forecast to decline to 1.9 and then remain at that level throughout the end of the time horizon, most provinces are forecast to have TFR increase to 1.9 and then remain at that rate through the end of the time horizon. Only Guizhou, Tibet, and Yunnan provinces have TFR above 1.9 historically that are forecast to decline to 1.9.

There are no known forecasts to compare the provincial forecasts for TFR with. The model's behavior looks good and without an available data source to update the historical data there is nothing that can be reasonably done to get the provincial model to match the 186 version.

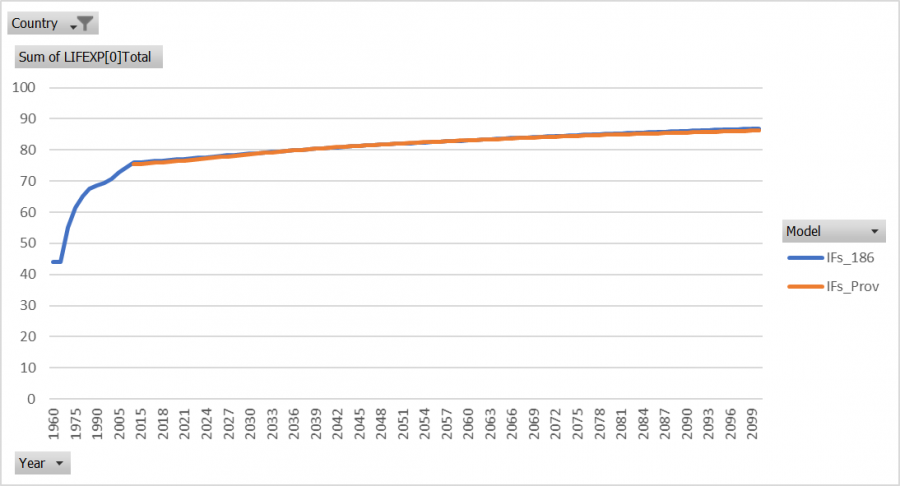

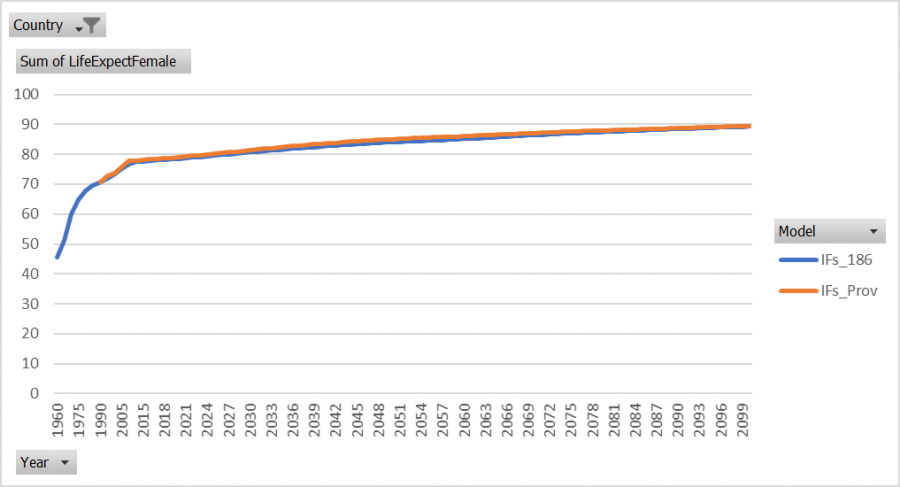

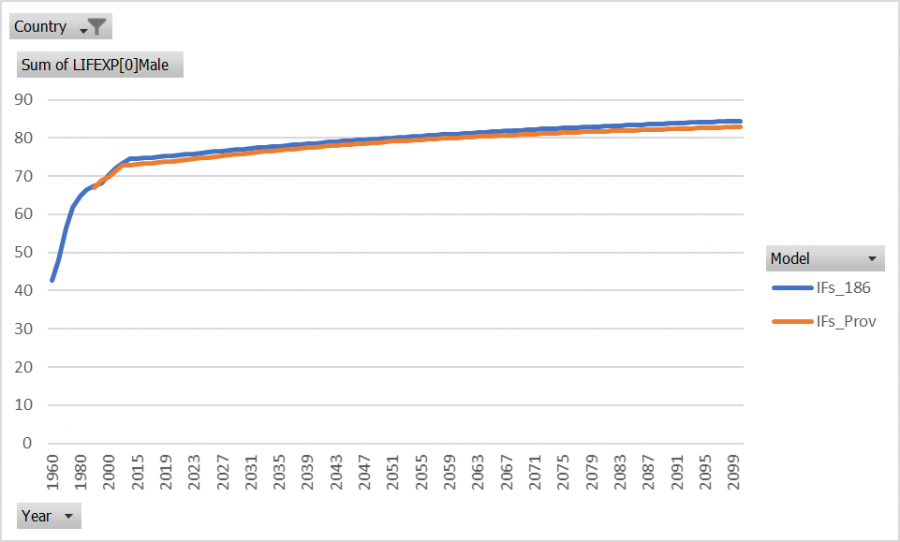

China's Life Expectancy

Life expectancy in China's provincial model is in line with the 186 model historically and through the end of the time horizon in the forecasts. Male life expectancy is slightly lower in the provincial model than in the 186 model, but female life expectancy and total life expectancy are nearly identical in the two models.

Total Life Expectancy

Life Expectancy Female

Life Expectancy Male

Economy

China's GDP

- ↑ Kam Wing Chan, Forthcoming in; The Encyclopedia of Global Migration, edited by Immanuel Ness (Blackwell Publishing, 2017).